In this blog, RECIRCULATE’s “Water for Sanitation and Health” team share their experience of enhancing the engagement, comprehension and buy-in of the local communities.

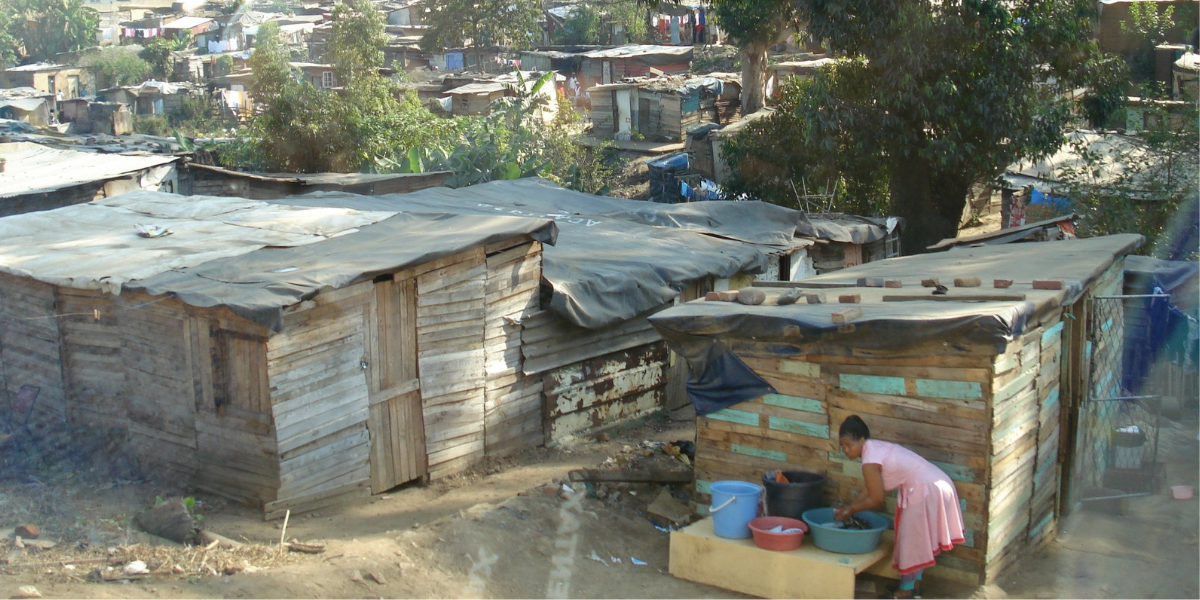

Maximizing the impacts of academic research hinges on the uptake of findings by communities, governments, policy makers, and other end users. In turn, that depends on communicating research findings to these end users in a comprehensible way. In our view, these problems remain a major challenge in the global south. As a consequence, our experience has been that when projects end there is usually no continuation, and research findings are rarely put in to practice. Communicating results clearly to end-users and so overcoming this lack of impact are key parts of RECIRCULATE’s “Water for Sanitation and Health” research. We focus on monitoring of drinking water quality in households at Gbegbeyise, a community in Greater Accra, Ghana. We have involved teenage boys and girls from Gbegbeyise in all stages of monitoring, and in doing so, we are confident that they will become powerful agents of behaviour change. Aged between 13 and 16 years, they are mostly Junior High School students with little hands-on experience in science.

In our water monitoring in Gbegbeyise we measure water quality at five different stages of the water journey into people’s homes. These include the main treatment point at the Ghana Water Company Limited / Booster Station, the feeder line before entering the community, the community stand pipe, water stored water in poly-tanks and finally, water stored in containers at the various households. However, our particular focus is contamination of drinking water between the standpipe and storage of water in the home. This is what is known as the “Last 100 metres” of the water journey.

Youths from Gbegbeyise worked alongside Research and Technical Officers and took part in collecting water at the household level. They also made on-site measurements of some physical parameters such as pH, total dissolved solids, temperature and conductivity using equipment purchased by the project, as well as residual chlorine and turbidity. Beyond that, they took part in administering the questionnaire and interviewing the households on how long they stored water in containers, how often refilling is done, and how often the containers are cleaned prior to filling with water. It was clear that parents, guardians, community elders and their peers were happy seeing their own children working with a research team to bring a change in their community. These experiences gave them a sense of belonging and could boost their interest in research work and science in general.

After the field experience in water collection and interviewing community members, the youth had the most exciting and memorable experience in their life when they joined RECIRCULATE Researchers at the laboratories of the Water Research Institute (CSIR-WRI), part of Ghana’s Council for Scientific and Industrial Research. The youth had the opportunity to observe and interact with Research and Technical Officers as they performed the laboratory analyses of the water samples collected from the community. In the Environmental Chemistry Laboratory, they were taken through determinations of pH, conductivity, colour, total dissolved solids, nutrients and a gist of analysing heavy metals, such as lead and copper. In the Microbiology Laboratory, the youth were taken through the various processes involved in determining bacteria present in the water samples from the community. These included preparation of growth media for indicator bacteria (total coliform, faecal coliform and E. coli), filtration of water samples through membrane filter using filtration manifold and vacuum pump and incubation of the filtered water samples on the various growth media at different temperatures.

We followed up the visit to the Microbiology Laboratory the following day, when we brought the teenagers back to observe how bacteria had grown. By observing the bacteria colonies on the culture plates and how they are counted, they could see at first-hand the extent of contamination of water collected from the community. When they saw the high quantity of bacterial colonies, including E. coli which is usually from a faecal origin, they were very curious to know the causes of contamination of water stored in the homes. We felt that this was an incredibly important step. By visiting our laboratory, and seeing with their own eyes the bacterial growth, the youths could immediately see the problems of using unclean containers to fetch water from storage containers, inadequate washing of storage containers and unhygienic way of storing water. What better way to help them understand the possible routes of contamination?

And what better way to empower youths to champion behaviour change back in Gbegbeyise? After seeing the bacteriological results, they have a unique insight with which to stimulate changes in how community members handle water quality at the household level. The teenagers were predominantly girls, and they seem to have developed the interest in studying more about contamination pathways and the important pathogens. Through them, RECIRCULATE will continue to make contributions to achieving many of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for years to come. That applies to particularly to SDG 3 (Good health and Wellbeing) and SDG 6 (Clean water and Sanitation), but also to SDG 5 (Gender equality) and SDG 10 (Reducing inequalities).

If our youthful change makers have learned a lot, then so have we. We have seen how observing the analyses and viewing live cultures on plates has empowered and motivated our youths to explain the findings to their peers, family and community at large. Coming back to those two challenges we highlighted at the start of this blog, perhaps the best way of “communicating results in a comprehensible way” is to allow the results to speak for themselves. Of course, we will complete all the measurements, do all the statistical analyses, write up the reports and papers. But does any of that matter to the youths from Gbegbeyise, now that they have seen things with their own eyes? We are confident that exposing the youngsters to the research process will lead to transformational and sustainable behaviour change in the communities. These are changes that will last long after RECIRCULATE’s GCRF-funded research is completed.

|

Mr Mark Akrong is a Senior Research Scientist with the Environmental Biology and Health Division (Microbiology Section) of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research – Water Research Institute (CSIR-WRI) in Ghana. He is a Microbiologist with ten years of experience. He obtained his Bachelor’s degree in Biological Science at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Kumasi, Ghana, MPhil degree in Environmental Science at the University of Ghana and currently a PhD candidate at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana. Mr. Akrong is part of the research team on the WP2 (Water for Sanitation and Health) of the RECIRCULATE project. |

|

Dr Kwadwo Ansong Asante is currently a Principal Research Scientist with the CSIR Water Research Institute (CSIR-WRI) in Ghana and a Visiting Researcher at the Lancaster University, UK. He is a Chemist/Ecotoxicologist and has been with the Institute since 1994. He obtained his B.Sc. (Hons) degree in Chemistry from the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (Ghana), M.Sc. in Environmental Chemistry and Ecotoxicology from Ehime University (Japan) and a Doctor of Science (D.Sc.) degree in Environmental Chemistry also from Ehime University (Japan). Dr. Asante co-ordinates the RECIRCULATE activities (Both Workpackage 2 and Workpackage 3) at the CSIR-WRI. |

All articles in The FLOW are published under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license, for details please read the RECIRCULATE re-publishing guidelines.